Executive summary

The Commonwealth Cyber Security Posture in 2025 (hereafter the ‘report’) informs the Australian Parliament on cyber security measures implemented across Australian government entities for the 2024–25 financial year. According to the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 Flipchart of Commonwealth entities and companies,[1] the Australian Government architecture comprised 102 non corporate Commonwealth entities (NCEs), 74 corporate Commonwealth entities (CCEs) and 18 Commonwealth companies (CCs). This is a total of 194 Australian government entities as of 30 June 2025.[2] [3]

The information included in this report is primarily derived from the annual Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) Cyber Security Survey for Commonwealth Entities (hereafter 'the ASD Survey'). In 2025, 94 per cent of federal government entities participated, which is the same rate as last year and equal to the highest participation rate. for the duration of this report. Data collected by ASD in the performance of its cyber security function supplements the survey findings.

For the purposes of this report, an entity's cyber security posture is considered against the following criteria:

- cyber security hardening: an entity’s implementation of cyber security technical mitigations, primarily the Essential Eight mitigation strategies, to reduce the likelihood of an information and communications technology (ICT) system being compromised[4]

- incident preparedness and response: an entity’s readiness to respond to a cyber security incident, and the actions taken when a cyber security incident occurs

- leadership and planning: an entity’s leadership adoption of cyber security mechanisms and cyber security culture.

Findings in this report indicate that, overall, Australian government entities have established corporate governance mechanisms to understand their security risks and prepare for cyber threats. The findings also indicate improvement is required in some areas and progress in others.

In particular, the report finds that:

- The proportion of entities that reached overall Maturity Level 2 across the Essential Eight mitigation strategies has increased. In 2025, 22 per cent of entities reached overall Maturity Level 2, increasing from 15 per cent in 2024.

- The number of entities reaching Maturity Level 2 has increased since 2024, but has not reached parity with 2023 when 25 per cent of entities reached Maturity Level 2. This is primarily due to a change that occurred in November 2023, when ASD increased and hardened the controls required to reach Maturity Level 2 in response to the threat environment. As a result, more work is required for entities to implement the updated mitigations.

- In 2025, 82 per cent of entities had a cyber security strategy, an increase from 75 per cent in 2024. Furthermore, 92 per cent of entities addressed cyber security disruptions in their business continuity and disaster recovery planning, an increase from 86 per cent in 2024.

- In 2025, 91 per cent of entities had a body of work planned that would improve their cyber security, of which 83 per cent had funded this work.

- The majority of entities had planned for managing a cyber security incident, and were ready to respond if needed. In 2025, 90 per cent of entities had an incident response plan, an increase from 86 per cent in 2024.

- In 2025, 87 per cent of entities provided annual cyber security training to their workforce, an increase from 78 per cent in 2024. In 2025, the number of entities that provided annual privileged user training was 45 per cent, a decrease from 51 per cent in 2024.[5]

- In 2025, 70 per cent of entities performed supply chain risk assessments for applications, information technology (IT) equipment and services, a decrease from 74 per cent in 2024.

- The percentage of entities reporting cyber security incidents to ASD remained low, with 35 per cent of entities indicating they reported at least half of the cyber security incidents observed on their networks to ASD in 2024.

- ASD has some visibility and telemetry across government agencies that assists with incident identification. In 2025, ASD notified government entities 223 times of potential malicious cyber activity.

Legacy IT presents significant and enduring risks to the cyber security posture of Australian government entities. In April and June 2024, ASD published guidance on Managing the Risks of Legacy IT that provides low-cost mitigations for legacy IT that government entities can draw upon in addition to their own strategies. In October 2025, ASD also released a suite of publications on modern defensible architecture that outlines how to consider security architecture and secure design fundamentals when investing in new or updating existing technical products and services. This includes when planning for the ongoing management and/or replacement of legacy IT.[6]

- In order to improve overall cyber security posture, it is recommended that entities:

- continue to implement the Essential Eight Mitigation strategies across their networks to at least Maturity Level 2

- prioritise effective logging to ensure entities are best placed to identify malicious activity

- implement strategies for managing legacy IT now and into the future

- ensure supply chain risk assessments are a core output for new IT procurements

- increase cyber security incident reporting and maintain a regularly tested incident response plan

- start preparing for Post Quantum Cryptography by locating and assessing algorithms that will need to transition to more secure forms of encryption.

About this report

This report is prepared in response to a 2017 Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) recommendation that ASD and the Attorney-General’s Department report annually to Parliament on the Commonwealth’s cyber security.[7]

Under the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF), NCEs are required to respond to the ASD Survey, while CCEs and CCs are encouraged to participate. In 2025, 101 NCEs responded to the survey along with 79 CCEs and CCs. This generated an overall participation rate of 94 per cent, the same participation rate as in 2024.

This report focuses on results from the 2025 ASD Survey, while also drawing on the 2023 and 2024 surveys for comparison. Data collected by ASD in the performance of its cyber security function has also been included as supplementary content. For instance, metrics gathered by ASD’s Cyber Hygiene Improvement Programs (CHIPs) about scanning capabilities for internet-facing systems has been included as this provides insights on progress against implementing cyber security standards and protocols.

This report does not identify entities by name. Any insight into the cyber security posture of individual entities made available to malicious cyber actors may increase the risk of those entities being targeted. All results have been anonymised and aggregated.

This report provides an assessment of the cyber security posture of Australian government entities as at 30 June 2025. It is the sixth such report to be tabled before Parliament.

The PSPF Assessment Report

As a response to the JCPAA’s 2017 recommendation, NCEs must also report on their security posture to their minister and the Department of Home Affairs. The PSPF Assessment Report 2023–24 refers particularly to the implementation of 16 government policies under the PSPF.[8] The Department of Home Affairs is responsible for the PSPF Assessment Report.

Two of those policies specifically address cyber security posture:

- PSPF Policy 13: Technology Lifecycle Management. This focuses on safeguarding ICT systems to support secure and continuous delivery of government business. It includes safeguarding ICT systems from cyber threats by effectively implementing principles from ASD’s Information Security Manual (ISM).[9]

- PSPF Policy 14: Cyber Security Strategies. This addresses strategies to mitigate common and emerging cyber threats. Since 1 July 2022, Policy 14 requires entities to implement the Essential Eight strategies to Maturity Level 2 under ASD’s Essential Eight Maturity Model and consider which of the remaining 29 Strategies to Mitigate Cyber Security Incidents are required to address the entity’s threats.[10]

The PSPF Assessment Report is an aggregated assessment of how Australian government entities implement the PSPF policies and, as such, complements this report. Some discrepancy between these results may be expected as the PSPF Report and the ASD Survey use different assessment models to determine cyber security maturity. The PSPF report covering the 2024–25 financial year is expected to be published in late 2025.

On 24 July 2025, the Department of Home Affairs launched a new iteration of the PSPF (PSPF Release 2025). Future iterations of the PSPF Assessment Report will assess against any new or updated requirements that will be introduced.

Cyber security hardening

Implementing technical cyber security controls helps Australian government entities defend their ICT environments against cyber security threats, thereby avoiding costly remediation, system downtime, lost productivity and loss of public confidence. This report refers to 2 measurements to assess entities’ implementation of technical cyber security controls:

- responses to the 2025 ASD Survey: Entities report on their progress implementing the controls recommended for each of the 8 mitigation strategies, or a compensating control, which are then used to attain a corresponding Essential Eight Maturity Level.

- Cyber Hygiene Improvement Program (CHIPs) results: CHIPs performs quarterly scans to detect key cyber hygiene indicators on entities’ internet-facing systems and services. These indicators are then used to assess whether entities are meeting cyber hygiene standards.

The Essential Eight

The Essential Eight outlines a set of 8 mitigation strategies designed to help Australian government entities reduce their vulnerability to cyber security incidents and the impact of incidents if they occur.[11]

The Essential Eight mitigation strategies are:

- patch applications: Entities should apply application patches that are released by vendors for vulnerabilities, or alternative vendor mitigations, in a timeframe appropriate to their risk of exposure to the vulnerabilities. Increased emphasis has been placed on patching applications that routinely interact with untrusted content from the internet.

- patch operating systems: Entities should apply operating system patches by vendors for vulnerabilities, or alternative vendor mitigations, as soon as possible or in a timely manner within the constraints of system uptime requirements.

- multi-factor authentication (MFA): Entities should use MFA, a security measure that requires 2 or more proofs of identity to grant access. A new minimum standard requires ‘something users have’ as well as ‘something users know’.

- restrict administrative privileges: Entities should limit the number of users with administrative privileges for operating systems and applications, as these users can make significant changes to system configuration and operation, bypass critical security settings and access sensitive data. Restricting administrative privileges makes it more difficult for malicious actors to elevate privileges, spread to other hosts, hide their existence, persist after reboot, obtain sensitive data or resist removal efforts.

- application control: Entities should implement application control, a security approach designed to protect against malicious code (also known as malware) executing on systems.[12] When implemented robustly, it ensures only approved applications can be executed.

- restrict Microsoft Office macros: Entities should ensure that all macros are checked by assessors, who are independent of macro developers, to confirm the macros are safe before they are digitally signed and/or placed within trusted locations.

- user application hardening: Entities should remove unnecessary system applications and place restrictions on application functions that are vulnerable to malicious use.

- regular backups: Entities should ensure there are regular backups of their systems and data as these will assist with recovery and maintenance operations in the event of cyber incidents.

The Essential Eight Maturity Model describes four maturity levels (0 to 3) for these strategies, which are determined based on the implementation of all the controls that ASD recommends, or appropriate compensating controls, for each strategy.

Higher levels of maturity are designed to defend against moderate-to-high degrees of sophistication in adversary tradecraft and targeting. As of 1 July 2022, the PSPF mandates that NCEs must implement all Essential Eight strategies to at least Maturity Level 2, and entities should consider if their threat environment warrants implementing strategies to achieve Maturity Level 3.[13]

ASD recommends that all Australian government entities implement the Essential Eight mitigation strategies using a risk-based approach. When strategies cannot be fully implemented, compensating controls may be used to manage the residual risk. The controls must provide an equivalent level of protection to the specific Essential Eight requirements for which they are compensating.

Updates to Essential Eight

In November 2023, ASD made substantial updates to the Essential Eight Maturity Model. Key focus areas updated included patching timeframes, increasing adoption of phishing resistant MFA, supporting management of cloud services, and performing incident detection and response for internet-facing infrastructure. A complete list of updates can be found at cyber.gov.au.

The updates address cyber security threats based on the known evolution of tradecraft used by malicious actors and ensure that ASD’s cyber security advice remains up to date and commensurate with the threat. The updates are also based on ASD’s experience in producing cyber threat intelligence, responding to cyber security incidents, conducting penetration testing and assisting entities in implementing the Essential Eight mitigation strategies. They reduce the risk of compromise by malicious actors and limit the impact if compromise occurs.

There were no updates to the Essential Eight Maturity Model in 2024–25.

Implementing the Essential Eight

The mitigation strategies that constitute the Essential Eight are designed to complement each other and provide coverage of various cyber threats. ASD recommends Australian government entities plan and implement controls to achieve at least the same maturity level across all 8 mitigation strategies. This is because achieving the same maturity level in each mitigation strategy will result in an overall maturity at that level. However, if the maturity level for mitigation strategies differ, the entity’s overall maturity level will be considered to be at the level of its least mature strategy.

According to the ASD Survey, the proportion of entities that have achieved Maturity Level 2 across all 8 mitigation strategies remains low. In 2025, 22 per cent of all entities achieved Maturity Level 2 or higher, an increase from 15 per cent in 2024.

At the mitigation strategy level, there is a considerable range in the percentages of entities that achieved Maturity Level 2 or higher for each strategy, as shown in Figure 1. In 2025, the number of entities that reached Maturity Level 2 or above increased for all 8 mitigation strategies compared to the 2024 results. Of the 8 mitigation strategies, 7 achieved a score of 46 per cent or higher.

The number of entities that reached Maturity Level 2 or above decreased compared with 2023 for 3 mitigation strategies: multi-factor authentication, application control and regular backups. This is due to updates made to the Essential Eight Maturity Model in November 2023.

Previous iterations of multi-factor authentication in the Essential Eight did not specify the types of authentication factors that could be used for multi-factor authentication. This led to the adoption of weaker forms of multi-factor authentication in 2023 that used biometrics, security questions, or ‘trusted signals’, none of which are recognised as valid authentication factors within standards. The requirement for phishing resistant multi-factor authentication is a higher technical standard than was previously required. This led to the decrease from 2023 to 2024 whilst entities implemented the new requirements. ASD is now observing steady uplift to the new multi-factor authentication standards.

Application control changes have been informed by malicious actors increasingly using living off the land techniques and insights gained from Essential Eight implementation assessments. Changes have focused on performing annual reviews of application control rulesets and implementing Microsoft’s recommended application block-list at a lower maturity level (previously Maturity Level 3, now Maturity Level 2). As the requirement to apply these controls at a lower Maturity Level was implemented, entities who had not applied these controls were no longer assessed as Maturity Level 2. ASD has observed an increase in 2025 as entities adopt this measure.

The November 2023 updates to the Essential Eight regarding regular backups impacted on the number of entities achieving Maturity Level 1 through Maturity Level 3. This update encouraged entities to consider the business criticality of their data when prioritising backups, rather than focusing exclusively on backing up what entities consider to be ‘important’ data. This refocusing of where backups should occur has impacted those entities backing up only what they consider as ‘important’ data. The number of entities adopting this measure has increased compared to 2024.

| FY 2022–23 | FY 2023–24 | FY 2024–25 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patch applications | 44% | 45% | 56% |

| Patch operating systems | 46% | 51% | 62% |

| Multi-factor authentication | 54% | 23% | 34% |

| Restrict administrative privileges | 40% | 31% | 46% |

| Application control | 57% | 36% | 48% |

| Restrict Microsoft Office macros | 64% | 68% | 81% |

| User application hardening | 48% | 37% | 49% |

| Regular backups | 70% | 59% | 67% |

Legacy IT and the Essential Eight

The use of legacy IT within a system can inhibit implementing the Essential Eight. Legacy IT is more vulnerable to cyber attacks as vendors do not support the development of security updates, or limit security services. Malicious actors may be able to compromise legacy IT and use it to gain access to more modern systems in the same IT environments.

Legacy IT can prevent entities achieving Maturity Level 2. In 2025, 59 per cent of entities indicated that their use of legacy technologies had impacted their ability to implement the Essential Eight, a decrease from 71 per cent in 2024. Entities reported, as shown in Figure 2, that the most significant reason for continued use of legacy IT was a lack of dedicated funding and lack of a viable replacement. Where legacy systems cannot immediately be replaced, ASD has guidance on mitigating the risks.

| % | |

|---|---|

| Lack of prioritisation | 16 |

| Insufficient dedicated funding | 34 |

| Lack of viable replacement | 18 |

| Insufficient skilled personnel | 2 |

| Other/not provided | 30 |

In 2024 and 2025, ASD released guidance setting out low-cost mitigations for legacy IT that organisations can draw upon in addition to their own strategies.[14]

Cyber Hygiene Improvement Programs (CHIPs)

The CHIPs is a data-driven and scaled capability to help Australian government entities understand and improve the security of their internet-facing attack surface. Using CHIPs, ASD systematically scans entities’ internet-facing infrastructure to find indicators of effective cyber security standards and secure protocols. Measurements include:

- security protocols on email domains[15]

- encryption on email servers[16]

- encryption on web sites[17]

- actively maintained websites.[18]

The data that follows identifies the proportion of entities’ internet-facing infrastructure that is implementing ASD’s recommended security measures. For these entities, at least 90 per cent of their internet-facing infrastructure has effective implementation of these measures for each category.

CHIPs results from May 2024 to May 2025

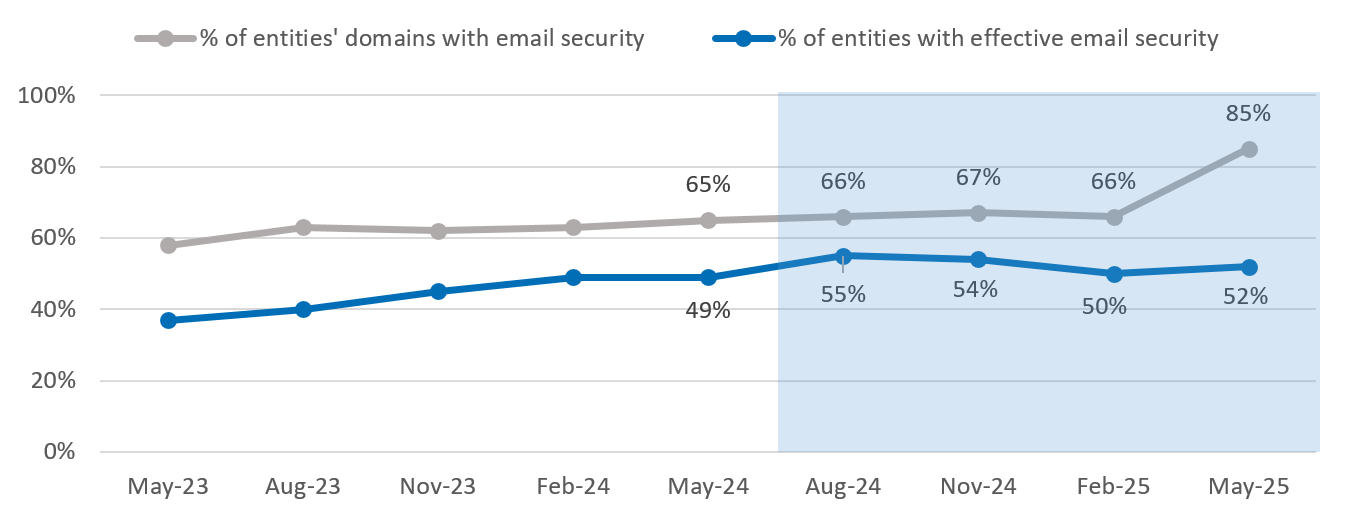

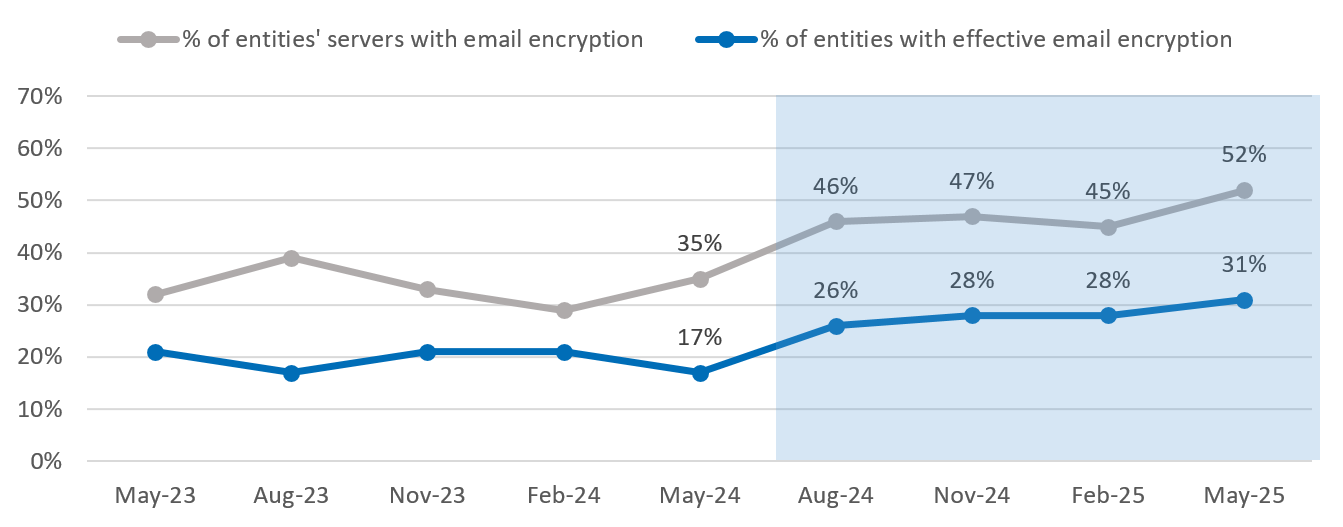

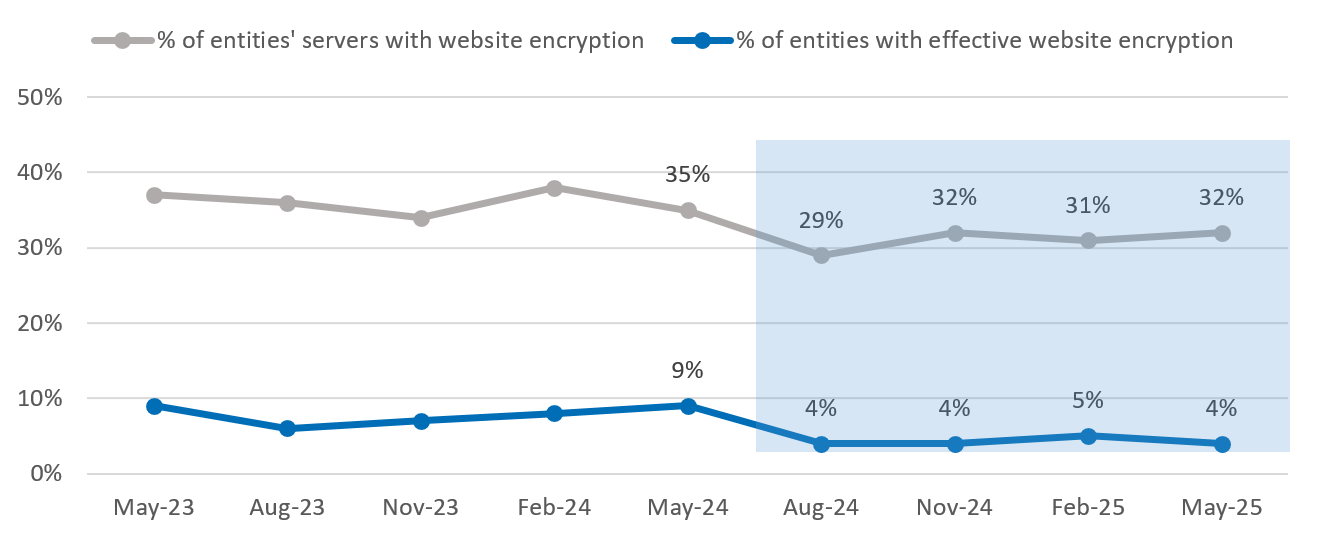

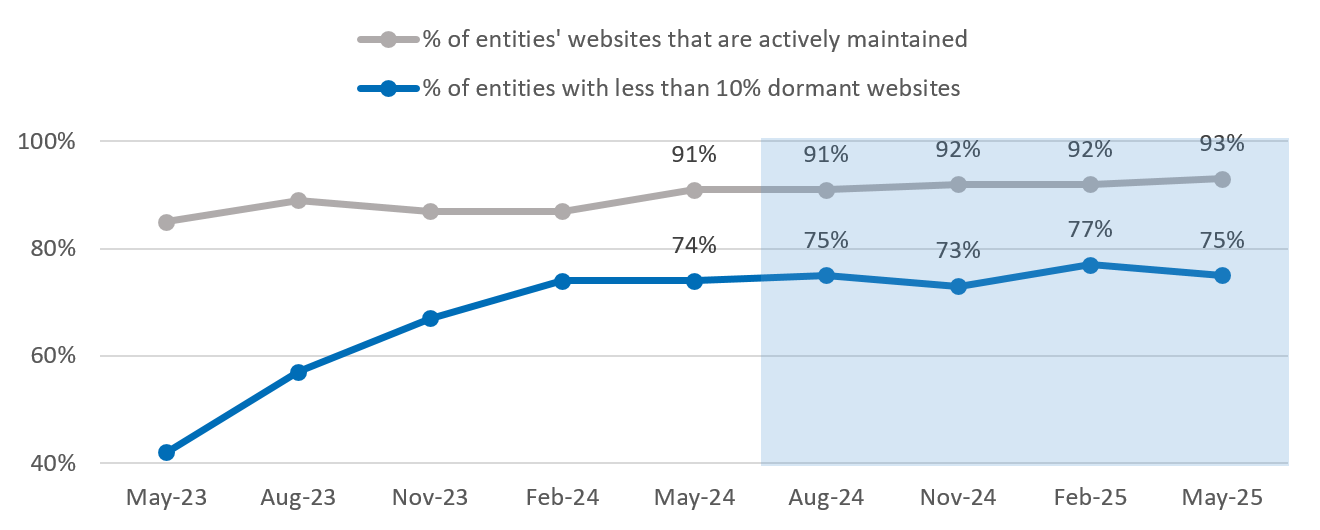

Across the servers and domains of all Australian government entities, email security, email encryption and actively maintained websites increased in 2025, as shown in figures 3 to 6.

Figure 3: Implementing email domain security protocols

Figure 4: Implementing email encryption

Figure 5: Implementing website encryption

Figure 6: Actively maintained websites

The proportion of domains implementing effective email security protocols increased significantly at the end of the reporting period, driven by key entities that operate many domains strengthening their cyber security. ASD tracked almost continuous improvement in this metric since first measured in 2018, at which time only 5 per cent of Australian government domains had effective email security protocols.

As shown in figure 5, between 2024 and 2025, the proportion of entities servers implementing effective website encryption decreased by 3 per cent. The cause of this is mostly due to an increase in ASD's ability to locate additional servers with inadequate encryption rather than a degradation in encryption settings on existing servers.

To improve their cyber performance against hygiene indicators, ASD recommends entities review their tailored quarterly CHIPs reports and attend to the detailed issues reported in them.

Incident preparedness and response

Australian government entities are a common target for malicious cyber activity. In the 2024–25 financial year, ASD responded to 408 cyber security incidents reported by entities. These reports represented 33 per cent of all cyber security incidents responded to by ASD. This is an increase from the 2023–24 financial year, when ASD responded to 406 reports, representing 36 per cent of all cyber security incidents.

Cyber security events and cyber security incidents are defined in the Information Security Manual, as follows:

- A cyber security event is an occurrence of a system, service or network state indicating a possible breach of security policy, failure of safeguards or a previously unknown situation that may be relevant to security.

- A cyber security incident is an unwanted or unexpected cyber security event, or a series of such events, that either has compromised business operations or has a significant probability of compromising business operations.

Cyber security incidents may result in denial of access to, theft of, or destruction of, systems and data. If not effectively managed, a cyber security incident may undermine public confidence in an entity and the incident’s remediation may consume significant resources.

Implementing incident preparedness and reporting

An Australian government entity’s cyber resilience is based on its ability to detect and manage cyber security events as well as the capacity to adapt to disruptions caused by cyber security incidents while maintaining continuous business operations.

The ASD Survey included questions designed to assess entities’ levels of preparedness to respond to a cyber security incident, their cyber event and incident detection capabilities, and their incident reporting behaviours.

Entities should plan for, and prepare to respond to, cyber security incidents. This includes identifying the data and systems essential to their business, accounting for cyber security incidents in business continuity planning, and developing and testing their incident response plan.

Responses to the survey indicate that 92 per cent of entities had identified their most essential systems and data and had planned for a cyber security incident, as shown in Figure 7.

| FY 2022-23 | FY 2023-24 | FY 2024-25 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % entities had identified the systems and data most essential to their business | 96 | 94 | 92 |

| % entities have an Incident Response Plan | 82 | 86 | 90 |

Developing, implementing and maintaining a cyber security incident register can assist with ensuring that appropriate remediation activities are undertaken in response to cyber security incidents. In addition, the types and frequency of cyber security incidents, along with the costs of remediation activities, can be used to inform future risk assessment activities.

Implementing a centralised event logging capability system enables incident aggregation, selection and analysis. In 2025, 90 per cent of entities had a centralised logging capability system.[19]

In August 2024, ASD led the publication of a joint Five Eyes product regarding best practices for event logging and threat detection.[20] Event logging supports the continued delivery of operations and improves the security and resilience of critical systems by enabling network visibility. This guidance makes recommendations that improve an entity’s resilience in the current cyber threat environment, with regard for resourcing constraints.

Under PSPF Policy 3, Australian government entities are required to report ‘significant or externally reportable’ cyber security incidents to ASD. The low rate of reporting may be due to a proportion of entities experiencing a high number of low-impact incidents, which they do not consider to meet the PSPF reporting threshold, as shown in Figure 8.

| FY 2022-23 | FY 2023-24 | FY 2024-25 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % entities that report at least 80% of incidents to their senior executive | 72 | 62 | 62 |

| % entities that report at least 50% of incidents to ASD | 42 | 32 | 35 |

In the 2024–25 financial year, entities reported the most incidents to ASD’s Australian Cyber Security Centre, compared to all other Australian sectors.

ASD maintains a national cyber threat picture that is informed by reporting of cyber security incidents by government and private entities. Aggregating cyber security incident data enables ASD to provide threat mitigation advice with the latest trends and threats posed by malicious cyber actors. Any degradation in the quantity or quality of information reported to ASD reduces our capacity to support the entity to mitigate the impacts of cyber compromise.

Leadership and planning

Strong leadership is essential in setting and maintaining a positive cyber security culture and for ensuring that cyber security remains part of an Australian government entity’s planning and everyday business. In particular, the Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) plays a key role in setting the strategy and direction of an entity’s cyber security program. CISOs are typically responsible for briefing senior leadership on their entity’s cyber security program and ensuring compliance with cyber security policy, standards, regulations and legislation.

The broader workforce also plays a key part in maintaining cyber security, and entities should provide ongoing cyber security awareness training to all personnel to help them best understand their cyber security responsibilities.

Implementing leadership and planning

Entities were assessed through a series of ASD Survey questions designed to provide indications of their cyber security leadership, planning and overall culture.

Over the 2024–25 financial year, survey responses indicated improvement in cyber security leadership and planning, as shown in Figure 9.

| FY 2022-23 | FY 2023-24 | FY 2024-25 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % entities that have a cyber security strategy | 73 | 75 | 82 |

| % entities that address disruptions due to cyber security incidents in business continuity and disaster recovery planning | 83 | 86 | 92 |

| % entities that have a planned body of work to improve cyber security | 89 | 88 | 91 |

| % entities that provide cyber security training at least annually | 78 | 78 | 87 |

| % entities that provide privileged user training at least annually | 39 | 51 | 45 |

In 2025, 82 per cent of Australian government entities reported having a cyber security strategy, an increase from 75 per cent in 2024. A cyber security strategy articulates an entity’s plans and priorities for cyber security uplift and mechanisms to manage cyber security risks. Achieving and maintaining effective cyber security mitigations requires investment, sufficient capability and clear objectives.

The cyber security posture of entities is affected by the risks associated with cyber supply chains. To mitigate potential increase to their security risk profile, entities should conduct risk management activities and risk assessments for each component of their supply chain.[21] In 2025, 70 per cent of entities reported having performed supply chain assessments for suppliers of applications, ICT equipment and services in order to assess potential impact to their system security risk profiles.

Effective cyber supply chain risk management ensures, as much as possible, the secure supply of products and services throughout their lifetime. This includes their design, manufacture, delivery, maintenance, decommissioning and disposal. As such, cyber supply chain risk management forms a significant component of any organisation’s overall cybersecurity strategy. In May 2023, ASD updated its guidance on how organisations can better manage their cyber supply chain risk management.[22]

Entities are also encouraged to prioritise the protection of their IT environment against the threat of a cryptographically relevant quantum computer (CRQC) now, even though a CRQC may not exist for some time. CRQC will render common public-key encryption protocols insecure. This means communications, information and data once thought secure, could be at a greater risk of compromise. All organisations are encouraged to be prepared by 2030 by moving to more secure forms of encryption.[23] In September 2025, ASD released Guidelines for cryptography that provides further information on how organisations can undertake this transition to post-quantum cryptography.[24]

In an effort to uplift their cyber resilience, Australian government entities participated in ASD’s Cyber Security Partnership Program. In 2025, 151 entities participated in the program.

Under the PSPF, Direction 003-2024 on Supporting Visibility of the Cyber Threat, published on 8 July 2024, participation in the program is now mandatory for NCEs. As at 30 June 2025, 99 per cent of NCEs had joined the program.

Conclusion

The findings presented in this report indicate that Australian government entities' cyber security postures were well established in some areas, but required improvement in others. In particular, over the 2024–25 period:

- The proportion of entities that reached overall Maturity Level 2 across the Essential Eight mitigation strategies increased.

- The number of entities that reached Maturity Level 2 increased for all 8 mitigation strategies.

- The proportion of entities applying effective email domain security improved, as did the proportion of entities implementing effective email encryption as measured by ASD’s CHIPs. The proportion of entities with actively maintained websites and implementing website encryption remained consistent.

- The majority of entities had planned for a cyber security incident and were ready to respond if needed.

- The percentage of entities reporting cyber security incidents to ASD increased.

- Indicators of cyber security leadership and planning remained high and showed improvement across entities.

- The proportion of entities that provided annual cyber security training to their workforce increased, while the proportion of entities providing privileged user training to their staff annually slightly decreased.

Report to Parliament 2026

The Commonwealth Cyber Security Posture in 2026 report to Parliament will be delivered by the end of 2026.

ASD services supporting Australian government cyber security

Cyber security hardening

Cyber security maturity assessment and uplift

ASD’s Cyber Maturity Measurement Program (CMMP) involves teams of ASD’s subject matter experts working with Australian government entities to assess their cyber security maturity against the Essential Eight, as well as assessing their broader cyber security posture. Entities are provided with a detailed report containing tailored advice and recommendations to improve their cyber security maturity.

The Cyber Uplift Remediation Program (CURP) is an enabler for high-priority Australian government entities to improve their cyber security posture. The objective of CURP is to uplift Essential Eight maturity, improve cyber security postures and remediate other cyber security vulnerabilities for entities. In partnership with entities, CURP provides skilled technical specialists who help implement security controls and provide further recommendations aligned with ASD’s findings. They also provide advice and services through complementary offerings.

In the 2024–25 financial year, ASD:

- carried out 7 CMMP assessments with high-priority entities

- provided 26 CURP uplift services for high-priority entities to improve their cyber security hygiene, awareness and implementation of a security roadmap, an increase from 17 uplifts in the previous financial year. Additionally, in July 2024, CURP piloted a light touch, short-term engagement model providing essential cyber security advice and assistance to entities, with 39 engagements undertaken.

Cyber Hygiene Improvement Programs

CHIPs is an open-source intelligence capability that analyses the cyber posture and hygiene of internet-facing systems and assets for government as well as critical infrastructure entities to identify cyber security vulnerabilities. CHIPs aims to improve Australia’s cyber security by building capabilities that provide a strategic advantage against threat actors. CHIPs provides quarterly reports to entities detailing their vulnerabilities and providing network owners with actionable information to inform cyber security posture-improvement activities. The program relies on a mixture of open source, commercial and directly collected data to provide situational awareness to ASD.

High-Priority Operational Tasking Cyber Hygiene Improvement Programs

The High-Priority Operational Tasking (HOT) CHIPs capability enables vulnerability assessment and triage with targeted data collection in response to critical vulnerabilities with Australian interests. The HOT CHIPs scans build ASD’s visibility of particular cyber security vulnerabilities across the Australian economic sector and offers network owners highly targeted, timely and actionable steps that can be employed to identify, reduce and mitigate system compromise.

During the 2024–25 financial year, ASD performed 478 HOT CHIPs assessments, up from 365 in the 2023–24 financial year.

Active Vulnerability Assessments

ASD’s Active Vulnerability Assessment (AVA) capability identifies security vulnerabilities that may be used by sophisticated cyber security actors. An AVA is a long-term engagement with high-priority customers to simulate the presence of a sophisticated cyber adversary while remaining undetected on the customer’s network. The outcome of the AVA activity allows customers to understand their vulnerabilities and test their responses when they detect unusual activity.

Hunt

ASD proactively conducts cyber threat hunt activities on priority Australian networks to detect unnoticed intrusions by sophisticated cyber actors. This service is offered to high-priority entities, including in support of events of national significance.

In the 2024–25 financial year, ASD conducted 2 hunt activities on priority Australian networks.

Incident preparedness and response

Alerts and advisories

ASD publishes alerts and advisories on cyber.gov.au to inform Australians about cyber security threats and mitigations. The ASD Alert Service is a subscription-based email service that informs Australians about the latest threats and vulnerabilities and how to address risks on their devices and computer networks.

Australian Cyber Security Hotline

The Australian Cyber Security Hotline ‘1300 CYBER1’ (1300 292 371) provides advice and assistance to Australians and entities impacted by cyber security incidents. The hotline is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

National Exercise Program

The National Exercise Program (NEP) works in partnership with Australian critical infrastructure and government entities to scope, plan, deliver and evaluate cyber security exercises to improve Australia’s overall cyber resilience. The NEP also delivers exercise management training workshops for Australian critical infrastructure and government entities.

In the 2024–25 financial year, ASD delivered 17 exercises for Australian critical infrastructure and government entities.

Incident response

ASD’s incident management capabilities provide tailored incident response advice and guidance to Australians impacted by a cyber security incident. For nationally significant incidents, ASD may also provide incident investigation support. ASD is not a law enforcement entity or regulator; however, it does work closely with these entities if needed.

Cyber Threat Intelligence Sharing

CTIS allows participants to share observable indicators of compromise (IOCs) at machine-to-machine speed. Participants can use these IOCs to identify activity on their own networks. The CTIS platform also allows participants to share the IOCs observed on their own networks with other CTIS partners.

In late 2024, ASD delivered a new in-house CTIS platform that further enhances industry and Australian government entities’ ability to share cyber threat intelligence. Prior to the transition, there were 33 government entities in the CTIS program. As of 30 June 2025, 35 Australian government entities are part of the CTIS program with 18 additional government entities in the pipeline to connect to the CTIS platform.

The PSPF Direction 003-2024 on Supporting Visibility of the Cyber Threat, published on 8 July 2024, mandates that NCEs using threat intelligence-sharing platforms also share cyber threat information with ASD.[25]

Australian Protective Domain Name System

The Australian Protective Domain Name System (AUPDNS) uses threat intelligence to build a block list of known and assessed malicious web domains. These domains are often used to distribute malware as part of malicious command and control channels or as part of a data-exfiltration channel.

AUPDNS prevents devices on subscribed networks from accessing the malicious domains on the block list, thereby interrupting potential malicious activity.

By June 2025, 55 Australian government entities had subscribed to AUPDNS, an increase from 49 entities in June 2024.

Leadership and planning

ASD's Cyber Security Partnership Program

ASD’s Cyber Security Partnership Program enables partners to engage with ASD and industry and Australian government partners, drawing on collective understanding, experience, skills and capability to lift cyber resilience across the Australian economy. ASD’s Cyber Security Partnership Program is a national program delivered through ASD’s state offices located around Australia.

The PSPF Direction 003-2024 on Supporting Visibility of the Cyber Threat, published on 8 July 2024, mandates NCEs to participate in ASD’s Cyber Security Partnership Program.

An ASD Network Partnership is available to organisations with responsibility for the security of a network or networks, either their own or on behalf of customers, as well as to academic, research and not-for-profit institutions with an active interest and expertise in cyber security.

Footnotes

- Flipchart of the PGPA Act entities and companies, PGPA Act Flipchart and List.

- Of the 194 Australian government entities, 2 entities were excluded from the ASD Survey. This is because the Australian National Preventive Health Agency, listed as an NCE, ceased operations on 30 June 2014. Additionally, ITC Technologies Pty Ltd, listed as a CC, was established as a holding company to acquire shares in CEA Technologies Pty Ltd to transfer the direct ownership to the Commonwealth, before being deregistered.

- The total number of Australian government entities increased from 190 at the end of the 2023–24 financial year.

- Find the Essential Eight at cyber.gov.au.

- Privileged user training is tailored to personnel with responsibilities beyond that of a normal user. Find the Guidelines for Personnel Security at cyber.gov.au.

- Find the guidance to Foundations for Modern Defensible Architecture, Investing in Modern Defensible Architecture, and Managing the Risks of Legacy IT at cyber.gov.au.

- JCPAA Report 467: Cybersecurity Compliance, Report 467. For the report, see aph.gov.au. The reporting responsibility was transferred to the Department of Home Affairs on 3 August 2023.

- Find PSPF policiesat protectivesecurity.gov.au.

- The ISM is a cyber security framework that entities can apply, using their risk management framework, to protect their IT and operational technology systems, applications and data from cyber threats. Find the ISM manual at cyber.gov.au.

- See section 14.2 of the 2025 PSPF.

- Find the Essential Eight at cyber.gov.au.

- In September 2024, ASD published an advisory on the risks of information stealer malware. Find the advisory at cyber.gov.au.

- Find out more at protectivesecurity.gov.au.

- Find Managing the Risks of Legacy ICT: Practitioner Guidance at cyber.gov.au.

- The minimum recommended email security protocols on domains is “The domain has a valid DMARC record, or has a valid DMARC record on its base domain, with an effective policy of 'reject' or 'quarantine'”.

- The minimum recommended email encryption is “The mail server supports Opportunistic TLS (STARTTLS), and supports at least TLS 1.2 (but may also allow TLS 1.1 and TLS 1.0 for backwards compatibility), and has a valid certificate, and offers at least one strong cipher, and offers no insecure ciphers”.

- The minimum recommended web server encryption is “The website sends an HSTS header when accessed, and HTTPS is enabled, and no weak or insecure cipher suites are used, and users are redirected to an HTTPS connection, and the oldest supported version of TLS is 1.2 or higher”.

- Inactive web servers are those that have not been updated for more than 4 years, that offer a default server configuration page, respond with server errors, are running on out of support software, offer an invalid certificate or do not support at least TLS 1.2.

- Previous editions of the ASD Survey asked entities to report whether they used a security information and event management (SIEM) platform.

- Find the Best practices for event logging and threat detection publication at cyber.gov.au.

- This may include application services, authentication services, backup services, desktop services, enterprise mobility services, gateway services, hosting services, network services, procurement services, security services, support services, and many other business-related services.

- Find Cyber supply chain risk management at cyber.gov.au.

- Find Planning for post-quantum cryptography at cyber.gov.au.

- Find Guidelines for cryptography at cyber.gov.au.

- See the PSPF Direction 003-2024 at protectivesecurity.gov.au.